Tuesday, May 30, 2017

Remembrance restores possibility to the past

Viktor Ullmann: Piano Concerto, Piano Sonata no. 7, Variations

Viktor Ullmann finished his Piano Concerto in Prague in December 1939, nine months after the Nazis had entered Czechoslovakia. By 1942 he was a prisoner in the concentration camp at Theresienstadt, where he was still able to compose, and where in 1994 he wrote his 7th Piano Sonata. But on October 16, 1944, he was moved to Auschwitz-Birkenau and two days later he was murdered. The loss to music was grave; Ullmann was only 46 when he died, and he might have been counted among the great composers of the century given a normal life and lifespan. There is no special pleading needed, since Ullmann's remaining works are of the highest quality, but neither should we forget the horrors from which this music was born. "Remembrance restores possibility to the past," said the philosopher Giorgio Agamben, "making what happened incomplete and completing what never was. Remembrance is neither what happened nor what did not happen but, rather, their potentialization, their becoming possible once again."

The team of pianist Moritz Ernst, the Dortmunder Philharmoniker and conductor Gabriel Feltz provide a vivid, atmospheric reading of the piano concerto, and Ernst's performance of the 7th Piano Sonata is passionate and mournful. The disc is filled out with a piece from happier days: the Variations and Double Fugue on a Theme by Arnold Schönberg, an intricate gem of intellectual, formal beauty.

Here is the second movement Andante tranquillo from the Piano Concerto: partial solace from the looming menace.

Sunday, May 28, 2017

At the end of a tragic day

Ives: Three Places in New England; Orchestral Set no. 2; New England Holidays

Memorial Day weekend is a good time to listen to Three Places in New England, which includes an especially poignant tribute by Charles Ives to the sacrifice of American soldiers in battle. This is deeply moving music, written in such a bold and original way that even today it makes one sit up and take notice; I can't imagine the effect it had when it was first played. The first of the Three Places in New England is entitled The “St. Gaudens” in Boston Common (Col. Shaw and his Colored Regiment); this is Augustus Saint-Gaudens' Memorial to Robert Gould Shaw & the Massachusetts 54th Regiment. This elegy is sombre, with precious little light falling on the doomed soldiers and their commander. All the martial tunes which Ives quotes, designed in the first place to uplift the spirits before battle, are intoned in a minor key, in the darkest of orchestrations, in the most grief-stricken rhythms. Ives was, I believe, as distraught about the dire history of African-Americans after the Civil War as he was about their defeat at the Second Battle of Fort Wagner. There is also great beauty, though, and we should pay special attention to this quotation: "Music is the best consolation for a despaired man." It's by Martin Luther King, Jr.

|

| Photo: Boston Globe |

| Harmony and Charles Ives in 1948. Photograph by Halley Erskine |

Ives is very well represented in recordings; there are many recordings of this music, some of which are good indeed. But only the best can keep the eccentricities from going over the top, and the sad bits from veering into the maudlin. We have in this new Seattle Symphony Media release one of the best. Ludovic Morlot walks this tightrope without seeming over cautious; indeed, the live recordings preserve a real feeling of occasion, while the SSM engineers provide life-like sound with real presence. Very highly recommended.

This disc will be released on June 2, 2017.

Saturday, May 27, 2017

An appealing mix of Brazilian piano music

Grace Alves: Keys to Rio

Along with relatively popular pieces by Ernesto Nazareth and Heitor Villa-Lobos, Brazilian pianist Grace Alves has done a real service in providing some rarities for piano from Marlos Nobre, Oriano de Almeida and especially Chiquinha Gonzaga, a great composer and social activist from the late 19th and early 20th centuries. While the Gonzaga pieces Gaúcho, Suspiro and Atraente might seem slight, they have real dignity and are very much pioneering efforts in the development of Brazilian popular music. Oriano de Almeida is from two generations after Villa-Lobos, but his music has the same Paris/Rio, modernism/folklore dynamic as Villa, though his style relies more on American jazz. This appealing music sounds more like Gershwin than his compatriot Villa-Lobos. His Valsa de Paris is really delightful. Marlos Nobre, Brazil's most distinguished living composer, provides two serious but accessible pieces that evoke the life and folklore of the North-East part of Brazil, as Villa-Lobos has often done. Alves plays with grace and power throughout, though without the final level of virtuosity and rhythmic control of Sonia Rubinsky or Nelson Freire. This is a fine first effort; I look forward to future recordings.

This review has also been posted at The Villa-Lobos Magazine.

Wednesday, May 24, 2017

Antheil's music, for a change

George Antheil, Symphony 4 & 5, Over the Plains

You don't have to go very far into most articles about George Antheil before you come across the phrase "bad boy of music". There you go, it's happened again! That's the first thing that comes to mind for many when the name comes up. Here are some of others that rise to the top nowadays, thanks to John Allison, that web comics chronicler of high culture (in Destroy History, a story about Hedy Lamarr in WWII Hollywood):

Antheil's reputation is, more than any composer I can think of, a victim of the non-musical components of his life. We seem to value his work with Lamarr in inventing frequency-hopping spread-spectrum communication more than his actual music. This would be fine if his music weren't so attractive and impressive. Chandos begins another orchestral music series with this new disc of Antheil Symphonies, and it's nice to finally zero in on the actual music for a change. Both symphonies are muscular, energetic mid-century symphonies with Russian finger-prints all over them, both via the movie-score milieu in which Antheil lived and direct from the latest works of Prokofiev and Shostakovich. But they also have tender moments and the kind of very fine details that are the sign of an original musician.

We used to make fun of how British actors sounded when they were playing Americans in the movies and on TV. Nowadays, of course, that's no longer the case; Ewan McGregor plays not one but two Minnesotans to perfection in Noah Hawley's Fargo. The hallmark of this Chandos release is authenticity, which of course is an important component of all music, not just Early Music. It's no special surprise that a British orchestra under a Finnish conductor can be so convincing in this music, since Antheil is writing in an International Style, where Berlin and Paris loom nearly as large as his later home, Hollywood. But getting the last nuance of the American side of the Trenton, New Jersey native Antheil is an impressive, McGregor-level, achievement. We can't tell for sure until the score makes its way to orchestras on this side of the Atlantic, but this world premiere recording of Antheil's Over the Plains has just the right Gary Cooper movie studio backlot feel that proves it's the real cowboy thing.

Chandos nails the authentic feel with the cover of their disc, taken from this vintage postcard of Hollywood Boulevard at Night, from Lake County Museum. Bring on the rest of Antheil's symphonies!

Monday, May 22, 2017

Masterpieces revealed

Villa-Lobos Symphonies 8, 9 & 11

Villa-Lobos wrote twelve symphonies, though only eleven of the scores survive, and he wrote them from early in his career (1916) to very late (1957, two years before his death). People have been warning us for a long time not to value Villa-Lobos's symphonies too highly. I know this; I've been one of them. Don't expect too much, was the message, his best works are for the guitar and piano, and in the Choros and the Bachianas Brasileiras series. Now that we're well into the Naxos Sao Paulo Symphony Orchestra (OSESP) series, led by Isaac Karabtchevsky, I'm beginning to think this particular piece of conventional wisdom might be wrong. These three symphonies sound familiar, sure, because they sound like Villa-Lobos. But even though I've heard all three a number of times, in the very good CPO series from Carl St. Clair and the Radio Symphony Orchestra of Stuttgart made around the turn of the last century, the music on the new disc sounds fresh and new and really quite amazing. This series is forcing all of us to sit up and take notice of a whole big chunk of Villa-Lobos's legendarily large output.

In his really excellent liner notes the guitarist and musicologist Fabio Zanon talks about how Villa's mature symphonies suffered because they were different from people's expectations and because of editorial problems with the scores. Though I hear the odd echo of the Choros from Villa's heyday in Paris in the 1920s, and plenty of call-outs to the Bachianas Brasileiras series of the 1930s and early 40s, the 8th, 9th and 11th Symphonies share something of a reboot feeling for the composer. Here he finally turns his back, more or less, on modernism, while doing the same, more or less, with the folkloric music that made his worldwide reputation. There's a neo-classical (not neo-baroque) sound that goes along with early classical symphonic structures. Zanon sees and hears both Haydn and Mozart in this music, with Beethoven and Schubert lurking around the edges. Having stripped down his orchestral music to the essentials, we're now more aware than ever of how Villa-Lobos has constructed the music. To be sure this is still music written for large orchestras, but there's no Brazilian percussion component, no prepared pianos or violinophones, and no over-the-top Romantic gestures. The first movement of the 9th Symphony is instructive. Villa zips out three themes in quick succession, gives them a quick run-through in his contrapuntal-light machine, and then, when you expect a fair bit of noodling, he winds things up abruptly, with a typical Villa-Lobos flourish. All done in less than four and a half minutes. I must say that I like the concise Villa-Lobos; it makes a nice change from the often over-blown padding of more than a few of his works. This is vivid, direct, lively music without empty gesticulation. With the varnish of score errors and outdated preconceptions removed, these three symphonies emerge as masterpieces.

A copy of this review is at The Villa-Lobos Magazine. The disc drops on June 9, 2017.

Sunday, May 21, 2017

The playfully profound music of Friedrich Gulda

Gulda Plays Mozart & Gulda

Improvisation is a process, according to Mike Nichols, that “absorbs you, creates you, and saves you.” In a superb in-depth New Yorker article about Nichols, John Lahr digs into his concept of improvisation. A lesson Nichols the director learned from his improv work with Elaine May was this: "To damn well pick something that would happen in the scene—an Event." Nichols goes on:

While you’re expressing what happens, you’re also saying underneath, ‘Do we share this? Are you like me in any way? Oh, look, you are. You laughed!That improv helped Nichols in his directing day-job is clear; it's also clear that it's a vital part of every classical musician's toolkit. This is about more than cadenzas and adding ornamentation in repeats; it's built in to the very DNA of both interpretation and composition. Mozart was a great improviser, as was Bach. The appreciation for Friedrich Gulda's genius, which has only grown since his death in 2000, is based to a large part on the unexpected places he takes us in the core repertoire of the piano. I recently listened straight through to the six CDs of his Complete Mozart Tapes, and was struck by how fresh and alive every single sonata sounded. Each movement was, in Nichols' sense, an Event.

This CD from BR Klassik, due to be released on June 2, 2017, comes from two live concerts. The first, from 2009, includes two Rondos for piano and orchestra swapped out by Mozart, for various reasons, from two of his Piano Concertos. In a feat that I'm sure Mike Nichols would have applauded, Mozart has taken some fairly pedestrian, even banal, themes, and spun them into a high level of entertainment, if not actual profundity. Gulda, with able assistance from Leopold Hager and the Symphonieorchester des Bayerischen Rundfunks, doesn't let down the side; he keeps the comedy moving, and he highlights the universal significance of the comic spirit. These two movements are a joy to listen to.

The second concert is actually a very special and famous one, and I'm quite surprised this portion of it has never been released before. It's the first 40 minutes or so of The Meeting between Gulda and Chick Corea, from June 27, 1982. This is Gulda playing solo, mainly his own improvisations, with a fine, typically dynamic version of Mozart's K. 330 sonata providing a kind of centre of gravity to the proceedings. Gulda's pieces aren't jazz, precisely, though he's clearly at home in several jazz idioms. They're really more like post-modern pastiches, with lots of Mozart, bits of Bach and blues and full-blown Romantic passages, mixed with a very Viennese-sounding sense of satire and parody. They're an important part of Gulda's playfully profound music.

The duet portions of The Meeting are available both on CD, DVD and YouTube. Here is Gulda's solo portion:

And here's Mike Nichols and Elaine May in a classic skit:

Saturday, May 13, 2017

Happy Centennial, Lou!

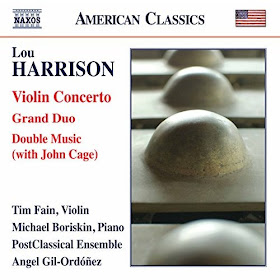

Lou Harrison: Violin concerto, Grand duo, Double music (with John Cage)

This disc (and this review) is well-timed. Today we celebrate the 100th anniversary of Lou Harrison's birth. There seems to be at least some small interest out there in what should be a major event, though I would have hoped for a bit more hype for one of my favourite American composers. In any case this splendid new disc from Naxos is a suitable marker for Lou's Centennial.

I recently came across this picture of the Surrealists in Paris:

|

| Man Ray, Hans Arp, Yves Tanguy, Andre Breton, Tristan Tzara, Salvador Dali, Paul Eluard, Max Ernst, Rene Crevel |

Harrison's own genius is pretty clear, nurtured by his mentor Henry Cowell, his teacher at UCLA Arnold Schoenberg, and later in New York, that great well-spring of American modernism Charles Ives. The Concerto for Violin and Percussion is a great introduction to Harrison's music, with its kitchen-sink "junk" percussion and surprisingly full-bodied emotion from the solo violin. Harrison acknowledged the influence of Alban Berg's Violin Concerto, about which he said "It really walloped me." The soloist Tim Fain plays with the required virtuosity as well as the sensitivity and musicality to scale the heights and plumb the depths of this remarkable work, one of the great American concertos, matched in Harrison's works by his Piano Concerto. Angel Gil-Ordonez's PostClassical Ensemble provide robust support, with an equal virtuosity on the percussion side. Fain is joined by pianist Michael Boriskin in Harrison's Grand Duo, which treats the piano very much in a percussive role, though considering how important percussion is to Harrison it's more a question of opening up new options for the pianist rather than limiting them.

The short but not slight Double Music makes a special impression in its seven minutes. It's the result of an intriguing collaboration with John Cage. Each composer provided music for two of the four players, based on a kind of temporal template, and the resulting work came together seamlessly. Chance, so important in Cage's music, had played its role perfectly. This piece nicely sums up mid-century American music: fresh and alive with many influences from around the world and from many time periods, as fun to listen to as I'm sure it is to play.

The short but not slight Double Music makes a special impression in its seven minutes. It's the result of an intriguing collaboration with John Cage. Each composer provided music for two of the four players, based on a kind of temporal template, and the resulting work came together seamlessly. Chance, so important in Cage's music, had played its role perfectly. This piece nicely sums up mid-century American music: fresh and alive with many influences from around the world and from many time periods, as fun to listen to as I'm sure it is to play.

Monday, May 1, 2017

Arresting visuals and compelling stories

Glenn Gould's story has as intriguing and appealing a visual element as an auditory one. From Gordon Parks' and Alfred Eisenstaedt's iconic photographs to the arresting images in Francois Girard's 32 Short Films About Glenn Gould, this is an important component in the carefully crafted performance art that was Glenn Gould's life. Now to add to this rich legacy we have a superb graphic novel (published in 2016 and just now out in an English translation) by Sandrine Revel, the comics artist and illustrator from Bordeaux.

In her website, Revel notes that Gould and his music meant a great deal to her since discovering him in college. "Glenn Gould m'accompagne depuis comme un ami, un double et par certains côtés je lui ressemble," she says, "Since then he has accompanied me as a friend, a double and in some ways I resemble him." This, I'm sure, is a common happening for those of us who didn't fit in during childhood, and who went through life "off tempo" as the new English version deftly translates the book's subtitle: "une vie à contretemps". Off-kilter Glenn is such an appealing character, and Revel gives us many touching scenes from his childhood, many very funny ones included. But it's the big, visionary pictures that impress me the most; Revel's vision is really impressive.

Besides her obvious skills as an illustrator, Revel brings some major story-telling chops to this project. Her vision is cinematic, and isn't bound to her book format; she tells multi-page stories and then tucks smaller, but often key, bits to break up the rhythm of the story she's telling.

Revel includes some impressive bibliographic back-matter: a full list of Gould's music that she listened to during the project, and good short lists for suggested further reading and for further viewing. Girard's film isn't included in the latter list, by the way, though it makes sense considering Revel's focus on primary sources: the music and video of Glenn Gould himself. This is very highly recommended, both for Gould fans and those who are just learning his amazing story.