Sunday, July 29, 2018

Defying the darkness of the unknown

Schubert: Symphony no. 5; Brahms: Serenade no. 2

In his Book of Friends Hugo von Hofmannsthal says "Joy requires more devotion, more courage than sorrow. Joy enjoins one to submit, precisely so far as to defy the darkness of the unknown." It's this joy that we hear over and over again in John Eliot Gardner's great recordings of Bach. He talks in his great book Bach: Music in the Castle of Heaven about "the festive joy and zest of this dance-impregnated music," and it's this zest that comes out in this new Schubert/Brahms disc recorded at a concert in The Concertgebouw on November 12, 2016.

It's perhaps easy enough to bring out the joyful side of Schubert's lovely 5th Symphony, which contains more beautiful melodies than some composers produce in a lifetime. Gardiner treats this very much as a classical work, which makes sense considering how much Schubert was in the thrall of Mozart at the time. That both Schubert and Mozart suffered in their lives more than the average composer makes this music even more miraculous; it truly does "defy the darkness of the unknown."

The two Brahms Serenades also come from a dark time, just following the death of Robert Schumann. As much as I love Brahms, I've never really taken to either of these works, but not because of any life circumstances. Rather, they both suffer a bit from being preparatory works for Brahms's symphonies to come. It's too calculated a move, I think, for such slight material. Gardiner gives it his best shot, as do his marvellous musicians, but the music doesn't really take off like the Schubert does, and furthermore it suffers from coming right after such a perfect piece. At the concert at The Concertgebouw the Brahms led off the evening, and the Schubert was the last work, following Beethoven's 4th Piano Concerto with Kristian Bezuidenhout. Still, serviceable Brahms and perfect Schubert still make for an entertaining and joyful hour of music.

This disc will be released on August 31, 2018.

Saturday, July 28, 2018

He has borrowed his authority from death

Hugh Levick: Island & Exile; Constellation; Remnants of Symmetry

Hugh Levick's new CD Remnants of Symmetry arrived at a perfect time for me; I was in the middle of Howard Eiland and Michael W. Jennings' masterful biography Walter Benjamin: A Critical Life. Levick's fine suite for piano and string quartet Island & Exile, played beautifully here by Wilhem Latchoumia and the Diotima Quartet, became the soundtrack for the sad tale of the great writer's wanderings, early memories and his eventual death.

Benjamin travelled to Ibiza a number of times, beginning in 1924, since he felt the same attraction to the Mediterranean as Goethe and other Germans had before him. The first movement of Levick's piece, entitled Ibiza, is no sunny idyll, though, but full of foreboding, a presentiment of the fateful events to come. Indeed, the second movement is Ultima Multis, a reference Benjamin makes in his essay The Storyteller to the inscription he saw on a sundial in Ibiza ("the last day for many"). "Death is the sanction for everything that the storyteller can tell. He has borrowed his authority from death." The following movement, A Berlin Childhood, makes reference to Benjamin's memoir Berlin Childhood Around 1900, which he calls a series of "individual expeditions into the depths of memory." This evocative piece takes us back to an earlier world just at the same time as Benjamin realized he would in all probability never be able to return. Levick ends with Exile, and as he tells the story of Benjamin's death at the Spanish border in 1940, fleeing from the Nazis, the music is full of the anger we all feel when we face the many, many stories of innocent people hounded from their homes, from those days until today.

The two other works on this disc are also very fine, full of incident and musically challenging. Constellation is a song cycle, performed here by Nicholas Isherwood with the Diotima Quartet. Texts are by authors as varied as William Blake and the 2nd century Gnostic writer Saint Thomas, and by Levick himself, I believe, though not credited in the liner booklet. Each of these songs makes a real impression, and stay with one for a long time after listening.

Arthur Koestler once said "Newton's apple & Cezanne's apple are discoveries more closely related than they seem." Science and art have fed off each other increasingly since the twin revolutions of post-Newtonian physics and modernism in the arts. With Remnants of Symmetry, featuring percussionists Daniel Ciampolini and Florent Jodelet and, again, the Diotima Quartet, Levick has set himself the most difficult of tasks: to tell the story of the creation of the universe, inspired, as he says, "by my lay reading" of current astrophysics. This is a subject that's been taken up by other composers in the past: I think of Haydn's The Creation, and before that, Jean-Fery Rebel’s Les Elements, but we have here a sophisticated interpretation of entropy, dark matter and silence, all in the context of the full palette of postmodern chamber music sounds.

Friday, July 27, 2018

Profound music from a teenage prodigy

Martha Argerich: The Successful Beginning: Ravel, Bartok, Chopin, Liszt, Prokoviev, Brahms, Schumann, Beethoven, Mozart

A new bunch of important historic recordings is being released by Profil's Edition Günter Hänssler on August 19, 2018, including a promising David Barenboim release, which I'll be reviewing soon. But I'm most excited about this 4-CD set of music by a talented teenager from Buenos Aires, Martha Argerich. Argerich shot to worldwide fame when she won the International Chopin Piano Competition in Warsaw in 1965, at age 24. But she was already a star-in-the-making when most of these recordings were made in 1960 and 1961, having won both the Geneva International Music Competition and the Ferruccio Busoni International Competition in 1957, at 16 years of age.

As a pupil of Friedrich Gulda - Argerich went to Vienna in 1955 to study with him - one would expect something special from her Mozart, but the performances of two great middle-period sonatas are quite astounding. The first movement of the A minor sonata K. 310 begins briskly, but Argerich soon draws back a curtain to show the composer working out dramatic themes that will soon blossom into The Abduction from the Seraglio and then his other great stage works. Argerich's control here is exemplary; she doesn't tip her hand too early, but she's ready to turn up the temperature when required. And the final section of the slow movement is played with a delicacy that rivals her teacher. The B-flat major sonata K. 333 has the same calm surfaces with hidden depths, but at a higher pitch. The slow movement of this work is a miracle: like a Watteau painting it seems at first to be something of exquisite prettiness, but it is soon exposed as something so much greater: the most perfect and awesome beauty.

Of the two concertos included, it's again the Mozart that impresses, and luckily Argerich here has the stronger support of the two, from the Kölner Rundfunk-Sinfonieorchester under Peter Maag, a favourite conductor of mine who showed up a lot on disc in those days. This is also from 1960, so Argerich is still a teenager, but she sparkles throughout, and makes this great concerto about so much more than glittering runs and soft-focus pastoral scenes from Elvira Madigan.

Argerich has the huge advantage of being teamed up with the great Ruggiero Ricci, the Centennial of whose birth we've celebrated this month. Ricci was in his prime when these Bartok, Sarasate and Beethoven works were recorded (which made him 41 or 42, if my calculations are correct). While the violinist has the spotlight on himself in the Sarasate, the other two works are more balanced, and Argerich definitely doesn't let down her partner. This is the beginning of a great career as a chamber music player, to go along with an equally great one as a soloist.

Naturally the last disc in the set is largely Chopin, and everything we've heard from her Chopin in later years is present in embryo at least. A 1955 Buenos Aires Etude has dreadful sound - the only really bad sonics on the disc - but even there you can hear Argerich's power and control and delicacy. What a great opportunity to be in at the beginning of this marvellous pianist's Odyssey!

Wednesday, July 25, 2018

Scotty, beam us up

Beethoven: Symphony no. 3; Ravel: Valses nobles et sentimentales

Giuseppe Sinopoli, the great Venetian conductor, has a reputation for cool and aloof interpretations, but I'm always as aware of his passionate undercurrents as I am of the cerebral arguments with which he builds his interpretations. Back in 2015 I noted the dramatic tension in his Schubert Unfinished Symphony with the Philharmonia Orchestra, contrasting it with a slightly underpowered version from Philippe Jordan. Sinopoli's white-hot recording of Schumann's 2nd Symphony with the Vienna Philharmonic (one of my all-time favourite discs) is another example. It was his experience in the opera pit, I believe, that provides the dynamic force of many of his orchestral recordings, and we hear it again in this release of a recording from Tel Aviv on October 28, 1993. There's plenty of drama in Beethoven's Eroica, but few recordings are as dramatically, indeed theatrically, shaped and shaded as this performance with the high-performing musicians of the Israel Philharmonic. Though Ravel's Valses nobles et sentimentales might seem at first glance to be more about music (in this case, Schubert's waltzes) than anything dramatic or theatrical, or indeed anything extra-musical at all. But after the composer orchestrated his original piano work, it was soon adapted as a ballet, Adélaïde, ou le langage des fleurs, with a plot taken from Dumas's La Dame aux Camélias. As one of the greatest interpreter's of Verdi's La Traviata, Giuseppe Sinopoli certainly knows his way around that story!

Sinopoli's day job may have been at the podium, but he had an astonishing range of interests and expertise, from medicine and criminology to anthropology and art collecting. There's a popular misconception that someone with a sophisticated intellectual life must be cold and analytical. It's like the common misinterpretation of the character of Spock in Star Trek's many iterations as exclusively cerebral. The half-Vulcan and half-human Spock is Gene Roddenbury's stand-in for all of the thoughtful people who pay attention to, and believe passionately in, the arts and culture and philosophy. To hold these not-at-all contradictory sides of our nature in balance is a worthy goal for us all, and the recordings of Giuseppe Sinopoli are powerful models.

This disc will be released in North America on September 7, 2018.

Tuesday, July 24, 2018

Soulful and jaunty light music of high calibre

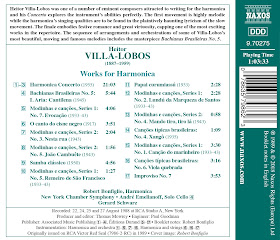

Villa-Lobos: Harmonica Concerto, Works for Harmonica & Orchestra

It's great to see this re-release on its way from Naxos, a label which has done such stellar service for Villa-Lobos over the years. This fine recording from Robert Bonfiglio that was originally released on RCA Red Seal back in 1989 will be re-released in a nice new package on September 14, 2018. It comes with a really useful liner-note essay by Bonfiglio, and as usual with historic re-issues from Naxos, it sounds great.

The Harmonica Concerto is one of Villa-Lobos's many late commissioned works. He wrote it for John Sebastian, the celebrated harmonica virtuoso (and father of the now more-famous John Sebastian, leader of The Lovin' Spoonful) in 1955. It's a pleasant work, tuneful as most late Villa-Lobos is. It's first theme is awfully close to Wally Stott's theme music for BBC's radio programme Hancock's Half Hour, but not to worry, since Villa-Lobos will always have another tune up his sleeve. Bonfiglio provides some virtuoso fireworks, especially in the third movement cadenza, but for most of the piece he's called on to provide soulful sounds, and he does, with emotion, charm and style. He has superb accompaniment from Gerard Schwarz and his New York Chamber Symphony (originally the Y Chamber Symphony, once resident at the 92 Street Y, which ran under Schwarz's leadership from 1977 to 2002).

As fine a work as the Harmonica Concerto is, the final two-thirds of the disc is perhaps even more interesting. It's comprised of arrangements (some by Bonfiglio and some anonymous) of Villa-Lobos songs for harmonica and orchestra. Of course there's a harmonica-and-cellos arrangement of the Aria to Bachianas Brasileiras no. 5 - how could there not be? You can never go wrong when arranging this evergreen piece as long as you have a suitably melodic instrument, and you don't meddle too much with the 8 cello parts. Schwarz's 8 cellists sound lovely here, as does Bonfiglio. The famous melody really does fit well with a harmonica. Bonfiglio includes pieces that Villa-Lobos cannibalized from his own catalogue when he put together music for his marvellous musical Magdalena in 1948. One of my favourite works here is the Samba classico that Villa-Lobos wrote in 1950 for voice and orchestra. By the way, this work was premiered by Villa-Lobos at the CBC in Montreal when the composer visited in 1958. This is soulful or jaunty light music of very high caliber. How nice to see this CD in the current catalogue once again!

This post is also at the Villa-Lobos Magazine blog.

Transcendence, transfiguration & redemption

The new Pentatone album of music from Vienna by Alisa Weilerstein, her first as Artistic Partner of the Trondheim Soloists, comes from a place of profoundly mixed feelings:

Schoenberg fled Vienna in 1934, four years before my grandparents escaped. So, as a young artist, nowhere in my imagination was the possibility of duality and contradiction made more manifest than in the history of that city. A culture that gave birth to some of the greatest achievements in the artform that I had chosen to pursue could, in the same breath, harbor sentiments and sanction behavior antithetical to music’s transcendent promise.This ambivalence is a common theme when writing about Vienna since the 1930s, by Jewish writers, or indeed anyone who has been paying attention to the often sordid political and social life of this great intellectual centre, once an Imperial capital. In "Thomas Bernhard, Karl Kraus, and Other Vienna-Hating Viennese", a fascinating article in the Paris Review, Matt Levin counts down a list of many great thinkers and artists - Robert Musil, Elias Canetti, Sigmund Freud, Ludwig Wittgenstein, Arthur Schnitzler, and more - and concludes, "...in some way, they all seemed to despise the city in at least equal measure to their affection."

For the last twelve years of his life Joseph Haydn lived in Gumpendorf, then a village on the outskirts of Vienna. After his many years away from the mainstream at Esterházy, he really wanted to be closer to the centre of the musical world, and that meant, in turn, Paris, London and Vienna. Alisa Weilerstein has a chance here to show off her considerable chops as a cellist in the two cello concertos that are undeniably by Haydn. But it's also Weilerstein as a conductor who shapes this music in the context of her thought-provoking program (a program that's beautifully laid out in a superb, long liner-notes essay by Mark Berry). We have here a picture of 18th century Vienna, one of civilized life before multiple revolutions brought down the power structures that had built the Austro-Hungarian Empire. But this is more than the usual nostalgic sentimental kitsch so common in Vienna, since Weilerstein brings out both Haydn's earthy humour and the folkloric musical roots of his music. Weilerstein and the players of the Trondheim Soloists have already developed a superb partnership in this repertoire, which also bodes well for future projects.

There's a huge gap between Haydn's Vienna and Arnold Schoenberg's Vienna, but in our post-modern world even the Second Vienna School can take on the same kind of nostalgic sheen that drapes pre-WWI society, of a different sort, certainly, but just as sentimental in its own way. Vienna has been called "an essential cockpit of modernism", but that revolution, which once seemed so close to our time, begins to recede into distant memories as we move into our new century. In his 1943 transcription of the 1899 original Schoenberg loses chamber music textures but gains in emotional intensity, assuming a very good performance, which we certainly get here. I always thought the famous Karajan recording from 1974 was way over the top, but this definitely isn't. Though it also packs an emotional punch, Weilerstein's version is responsible in the way that Karajan's version wasn't, clear-eyed about the beauty of the music but also the horrors into which Vienna would descend.

What a thoughtful and impressively musical disc this is!

This recording will be released on August 24, 2018.

Sunday, July 22, 2018

Into my sad heart

Linda Leonardo: Eterno Fado

I was excited when I saw this ARC Music album of music by the superb Fado singer Linda Leonardo, entitled Eterno Fado, which is due to be released on July 27, 2018. Alas, it's a re-issue of her great 2007 release, which was called The Mystery of Fado, albeit one with fine production values. A beautifully designed liner booklet includes the lyrics of each song, with English translations, and as a bonus, some poems by Leonardo, again with translations. As well, the booklet includes complete information about the musicians supporting Leonardo, an important reason for the very high quality of this album. Though the soul of Fado is in the expressive, emotional voice part, it's set off and provided with further depth by the accompanying Guitara Portuguesa and Viola (classical guitar), and occasionally other strings and piano. The group supporting Leonardo for most of the songs in this session are Diogo Clemente, guitar, José Manuel Neto, Portuguese guitar, and Marino de Freitas, bass. The CD was recorded at the famous Pé de Vento Studio in Foros de Salvaterra, where so many great Fado albums were recreated.

Nearly every song here is a classic, full of saudade in the lyrics, but with an unmistakably upbeat rhythm keeping outright depression at bay. A standout is the 12th track, Chamar fado á solidão, with music by bassist Marino de Freitas and lyrics by Tiago Torres da Silva.

But I wouldn’t have wanted to sing,Though I would have preferred a brand-new Linda Leonardo release, I can whole-heartedly recommend this marvellous CD, and every one of the 14 songs included in it.

Without having brought Fado

Into my sad heart.

Saturday, July 14, 2018

Something in the water

Leonard Bernstein Broadway to Hollywood: Candide Overture, On the Waterfront Symphonic Suite, Fancy Free Ballet, West Side Story Symphonic Dances, Two Dance Episodes from On the Town

The idea that an orchestra has a home-town composer "in their blood", and are the best, most authentic interpreters of his or her music probably doesn't always, or even usually, hold up to close scrutiny. Aside from sheer familiarity, and with a nod to local traditions handed down from orchestral player to player over the years, today's high musical standards and player mobility has resulted in a much more globalised and homogenised classical music scene. Even in the past we heard great Villa-Lobos from Paris, great Shostakovich from New York, and great everything from Cleveland. But what about the scores of Leonard Bernstein originating on Broadway and in Hollywood, both of which have their own traditions? This 1993 concert from the Hannover Philharmonic under the direction of the Scottish conductor Iain Sutherland is a powerful example of getting pretty much everything right, every nuance and subtle rhythm, in a completely idiomatic, authentic performance that serves Leonard Bernstein's fabulous music so well.

This isn't as surprising as it seems when you pull some threads and see the connections. Bernstein himself has international roots, with European teachers at Harvard and Curtis, and a thorough grounding through his mentors in Parisian modernism. Broadway's musical traditions might seem 100% New York, but of course there's always been a special connection through London's West End theatres to the great heritage of English light music. Similarly, Hollywood's direct pipeline to central European music through such composers as Steiner, Korngold and Herrmann adds another loop. Bernstein is an heir to all of these traditions, as is Iain Sutherland, and the very fine players of the Hannover Philharmonic play the hell out of all this music. One of the highlights is the Symphonic Suite from On the Waterfront. I've always thought that after Elia Kazaan's direction, Budd Schulberg's story and Marlon Brando's performance, it was Bernstein's music that helped put this film over the top into greatness. The band has a lot of fun with the Fancy Free suite, showing great range, from small jazz combo through big band to complete orchestra, all of which swing.

Somm does its usual fine job with remastering, documentation and presentation, though they missed out on the credit for the cover photograph. It's by Al Ravenna of the New York World Telegram & Sun, from 1955, in the Library of Congress's collection.

This disc will be released on August 17, 2018.

Thursday, July 12, 2018

The precision of ideas

Beethoven: Complete String Quartets

I've been keeping an ear on Audite's complete Beethoven String Quartets series with the Quartetto di Cremona as they've been released since the recordings began in 2012, though I missed a few along the way. Now with this release of the complete quartets on 8 CDs I can take a long close look at the well-received series from this fine group, who hail from the city of the great stringed instrument-makers.

These are elegant, controlled performances, though without the final burnished sheen of the Amadeus or Alban Berg Quartets. "Without minute neatness of execution," William Blake once said, "the sublime cannot exist! Grandeur of ideas is founded on precision of ideas." The "final minute neatness" is not here, or at least not all the time, though that neatness would in an case wear a bit thin through a full nine hours of music. The string quartets of Beethoven go on a meandering voyage through his own messy life, from his early days nearly to his death. This music, which began in the candle-lit salons of the Ancien Régime, emerges in the worlds of fashion and celebrity that made him a household name throughout Europe, and comes to an end in the squalor, regret and frustration of his final years. It's all too real to have the same Platonic existence of the music of Bach, though that doesn't make it any less grand, or sublime, in the Blakean sense. The Cremona musicians connect with this real-life Beethoven, his folk-song references, musical jokes and sentimental tags. And yet they're still able to bring a nearly full account of the soaring genius of the late quartets. Consider the Quartetto di Cremona a reliable guide to one of the greatest of all musical journeys.

|

| A sketch for Beethoven's op. 131 String Quartet, from 1826 |

Saturday, July 7, 2018

Fully Romantic Bruch without sentimentaliy

Max Bruch: Scottish Fantasy, Violin Concerto no. 1

Joshua Bell was only eleven years old when he learned his first major concerto, the Bruch Violin Concerto no. 1, and only 21 when his premiere recording with the Academy of St. Martin in the Fields under Neville Marriner (Bruch no. 1 plus the Mendelssohn) was released in 1988 to great acclaim. Thirty years later Marriner is gone, but Bell, who took over as Music Director of ASMF in 2011, is back playing Bruch with his band. This time he's included the Scottish Fantasy, my favourite Bruch piece (and my Mom's). While the new recording of the Concerto follows Sir Neville's tempi in the outer movements, Bell is brisker with the middle Adagio, though there's no lack of sentiment in the new recording. More importantly, Bell eschews any sentimentality in both Concerto and Fantasy, keeping to the classical bones of these great works while tending to the Romantic flesh. This is a highly recommended release.

Sunday, July 1, 2018

Greatness in musical partnership

Mravinsky Edition, volume 3: works by Tchaikovsky, Bach, Weber, Wagner, Scriabin, Kalinnikov, Bruckner, Shostakovich

I've come to historic recordings fairly late, but I've had such good luck with recent releases that I'm beginning to search them out. This 6 CD set, the 3rd volume in Profil's Mravinsky Edition, is a superb example of well-documented remastered recordings of special significance. It's easy enough to filter out sonic shortcomings when the performances are so vital. Mravinsky had a lifelong relationship with the Leningrad Philharmonic Orchestra, and it's fascinating to hear the development of their musical partnership from 1938 to 1961. The obvious highlights in this package are the Tchaikovsky Symphonies #4 and (especially) #5 and a blistering performance of the Shostakovich 8th Symphony. But I was completely bowled over by Mravinsky's take on Bruckner's 8th Symphony, which I've been listening to a lot lately. In my review of Mariss Jansson's recent recording, I talked about the balance in Bruckner 8 between what Vincent Van Gogh referred to as "Tranquility of Touch" and "Intensity of Thought". It's no surprise that Mravinsky comes down on the intense side. Shostakovich biographer David Fanning describes just this intensity:

The Leningrad Philharmonic play like a wild stallion, only just held in check by the willpower of its master. Every smallest movement is placed with fierce pride; at any moment it may break into such a frenzied gallop that you hardly know whether to feel exhilarated or terrified.An outstanding production all around.