"We are homesick most for the places we have never known."

- Carson McCullers

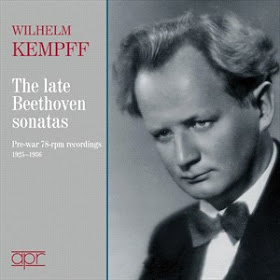

I don't normally listen to this kind of historical release, but this new double album (to be released August 26, 2016) from Britain's APR Recordings has plenty of musical interest, and there are a number of nostalgia hooks for this baby boomer. This is in spite of the fact that I didn't come across Wilhelm Kempff until his third wave of Beethoven sonata cycle recordings: the stereo releases from the mid-1960s, which followed the mono ones of the mid-1950s, and the partial cycle on 78rpm recordings from the 20s and 30s, a generous selection of which are included in this release. I've talked before about the importance of Kempff's cycle in my early discovery of Beethoven, but like the LP-toting hipster of today, this is also about a medium that pre-dates even my advanced years: the 78 rpm record. I am old enough to remember the thrill of holding a heavy disc in my hand, even if it was by then from far in the past, and hearing the pops and clicks and steady hiss along with a sound that was more compressed and limited than we're used to then or today, but often somehow fuller and richer at the same time.

We perhaps take for granted the sterling work of the early recording restoration specialists; it's quite remarkable how much piano sound there is in the best of these tracks, and even in the worst of them, the 1928 acoustic recording of op. 101. The Kempff style comes through loud and clear: more lyrical than histrionic; more thoughtful than dramatic; more Greek, as they say in the Sicilian portion of The Godfather, than Italian. The recording technology of the mid 1930s was good enough that you can listen to the sonata op. 110 (recorded in July of 1936) and at some point completely forget the provenance of the recording. Let's not forget to praise the re-mastering again! There are even some musical advantages to these early recordings: a fresh and spontaneous feeling that comes with a bit of the pioneer spirit. Three of these sonatas (op. 81a, 90 and 101) are the very first to be put on record by any artist. To be sure there are drawbacks beyond the sound: the lack of repeats (which allows the longer sonatas to fit on fewer records) emphasizes what some have argued is a lack of gravitas in Kempff's playing, especially in the slow movements. And the short playing time of each record side (the Hammerklavier was on five 78s, or 10 sides) meant some sonata movements were divided into chunks during the recording process, which militates against the presentation of a coherent architecture for Beethoven's awesomely large musical structures. But technology isn't everything - the critical consensus is that Kempff's mono cycle not only is a greater interpretation, but even sounds better than the stereo made the following decade. These performances are a valuable portrait of the early days of recording and of a Beethoven genius, and they're a blast to listen to.

No comments:

Post a Comment