Reviews and occasional notes on classical music

Reviews and occasional notes on classical music

"Music, both vocall and instrumental, so good, so delectable, so rare, so admirable, so super excellent, that it did even ravish and stupifie all those strangers that never heard the like." - Thomas Coryat, after hearing 3 hours of music at the Scuola di San Rocco in Venice, 1608.

"Music, both vocall and instrumental, so good, so delectable, so rare, so admirable, so super excellent, that it did even ravish and stupifie all those strangers that never heard the like." - Thomas Coryat, after hearing 3 hours of music at the Scuola di San Rocco in Venice, 1608.

Saturday, April 30, 2016

Suzuki's Stravinsky

This is a disc I was so excited to see. I've been a huge fan of the epic Bach project on BIS by Masaaki Suzuki with his amazing Bach Collegium of Japan. I had heard that Suzuki was beginning to conduct new repertoire with various orchestras, and this project, with the Tapiola Sinfonietta, is the first to show up on CD. It's due to be released on June 10, 2016, though you can buy it now in FLAC or MP3 at eClassical now.

My favourite Pulcinella on disc is Pierre Boulez's recording of the full ballet on CSO Resound; my 2010 review is here. Suzuki has only recorded the suite, but his version is very fine. He takes, not surprisingly, a much warmer view of this music than Boulez, who admits to disliking Stravinsky's neo-classical music but making a exception for Pulcinella. There is nothing but love in Suzuki's version; he's always been one to wear his learning lightly, so it's no surprise that this music swings so beautifully while keeping true to Stravinsky's oddly time-warped version of 18th century music. This music is great fun in Suzuki's hands, but also heart-warming, and sometimes even moving.

I don't believe Boulez conducted either Apollon Musagete or the Concerto in D, so we can't compare his drier approach to Suzuki's. This mordant music works well with a more lyrical approach, though, and I could listen to both of these works often, as I have already. The Tapiola Sinfonietta is in excellent form, and though I haven't yet experienced the surround-sound version on the SACD, the stereo sound is full and rich and pleasant to listen to. All of those times, and many more in the future!

Wednesday, April 27, 2016

Music of solace

Earlier this month I took the long way around - through Bob Dylan and Jimi Hendrix - to a discussion of J.S. Bach's creative adaptation of Giovanni Battista Pergolesi's Stabat Mater. Now we have this beautiful version of Tilge, Höchster, meine Sünden, BWV 1083, by my favourite bunch of Cantata musicians, Bach Collegium Japan, under Masaaki Suzuki. Though we don't know anything about the event for which this was written, I believe Bach felt solace might be found in the Italian grace and beauty of Pergolesi's work, though there isn't much Italian sunshine to be found in the heart-breaking sadness of the music and the highly personal words of Mary mourning for her Son. Bach also provides uplift in his substitution of the Psalm 51 for the 13th century poem Stabat Mater. A spirited exchange between soprano and alto goes like this in the original:

Fac, ut árdeat cor meum

in amándo Christum Deum

ut sibi compláceam.

Make me feel as thou hast felt;

make my soul to glow and melt

with the love of Christ my Lord.

In Bach's version, the music is much less driven; it's conciliatory and in the end joyful. There's also been a significant change in the words:

Laß mich Freud und Wonne spüren,

daß die Gebeine triumphieren,

da dein Kreuz mich hart gedrängt.

Your cross pressed hard on me; now let me feel joy andThe joy comes through perfectly in this version of the work, as it nearly always does in Suzuki's performances. It's there as well in the more formal Trauerode (Funeral Ode) BWV 198, written for the funeral of Christiane Eberhardine, the wife of the Polish King and Elector of Saxony Augustus the Strong. This is highly sophisticated music, based on highly sophisticated theology. Whether solace for grief is sought in music or in words, it never hurts to have Bach involved.

bliss and let the body triumph.

Tuesday, April 26, 2016

Rule Britannia

It's British Music week here at Music for Several Instruments. I'm listening to three new Chandos discs: a 2-CD re-issue of British Cello Concertos with Raphael Wallfisch, volume 2 in the Overtures from the British Isles series from Rumon Gamba and the BBC National Orchestra of Wales, and another volume 2, in Tasmin Little & Piers Lane's British Violin Sonatas series. Before we get started, then, just a reminder of what went before, or as they say on TV,

Previously, on British Music from Chandos....

Previously, on British Music from Chandos....

The first disc in the Tasmin Little/Piers Lane series, released in June of 2013, is marvellous, and this model bodes well for the new disc, due to be released in June 2016. The full-blown pastoral yumminess of Howard Ferguson's Violin Sonata is presented to its best advantage, without sentimental flourishes or ironic winks. Benjamin Britten flexes his muscles in his early Suite for Violin and Piano; grown-up music from a 21-year-old. This is definitely a Continental side-trip for Little and Lane - it was chosen for a Barcelona Contemporary Music festival by Anton Webern and Ernest Ansermet - and they provide the requisite sophistication here. The William Walton pieces are a bit in both camps, looking back with nostalgia and ahead with spikes out, but again the shift in tone is handled very well, with sensitivity to this more introverted, cerebral music.

The first of the Rumon Gamba Overtures discs, from January 2014, was also a real success, and with some quite obscure music:

This disc got rave reviews from Britain - I'm not sure it was heard much anywhere else. These are well-crafted late Victorian overtures, and together they conjure a time when classical music, of the lighter variety, to be sure, was truly popular. We're all off to the concert!

Saturday, April 23, 2016

A Grand Tannhäuser

Tannhäuser is precariously balanced on the sacred and profane axis, both in its subject and in the tortured history of its productions in the musical capitals of Europe. The pure musical tradition of German song is contrasted with the decadent Grand Opera of Paris, with its focus on crowd-pleasing effects and Jockey Club-sponsored ballerinas. Wagner's theme may be redemption - his theme is always redemption - but his heart is in the spectacle. That's why I enjoyed this production so much; it turns renunciation and atonement into pageantry.

Musically this is quite outstanding. Daniel Barenboim, conducting of one of Europe's great orchestras, sets the stage for a great evening of theatre. In the overture and the introductions to Acts II and III the way that the camera pans through the orchestra, looking over Barenboim's shoulder, is as dramatic as anything on stage. When he stands to bring out a particularly thrilling phrase it's electric. The singing is really excellent as well, with a dramatically assured Peter Seiffert grounding the opera, between the two poles of slinky mezzo Marina Prudenskaya as Venus, and soprano Ann Petersen, radiant in a Grace Kelly gown, as Elisabeth. Rene Pape as Hermann, and especially Peter Mattei as Wolfram von Eschenbach are superb singers and equally good actors.

Wagner sweated bullets trying to integrate the ballet conventions of the Paris Opera into his story of Minnesingers. This production by Sasha Waltz (is there a better name for a choreographer?) is no where close to being consistently successful, but when one of her many dance or dramatic ideas works, it works big-time. The Venusberg Scene in Act I takes place within a metal tube that looks like an eye. Partially-clad dancers cavort inside, looking like something from the cutting room floor of Woody Allen's Everything You Wanted to Know About Sex, but Were Afraid to Ask. Then the lighting changes, and the scene is reminiscent of a James Bond credit sequence. But at some point things come together, and all of a sudden the scene becomes fabulously sexy and incredibly beautiful. What happened? I was just snickering a minute ago! When Prudenskaya and Seiffert come sliding down the tube, we have a moving presentation of Tannhäuser's long dream of sensuality.

This is such an eclectic production, and it's all the better for it. There's a natural shift from Venusberg to the Minstrel's Hall on the Wartburg, and Waltz sets us up in a brightly lit Art Deco Hollywood set that's full of one per centers looking elegant. Here is where the integration of dance really pays off. The story of the musical competition can come across as a dullish Medieval German episode of Glee, but Waltz turns on her inner Busby Berkley, and everything sparkles. I don't know if this is deliberate, but when groups of singers and dancers stand frozen for a while, I was reminded of Alain Renais's Last Year at Marienbad. Both that film and Wagner's opera ground their drama in deeply ambiguous dream states.

Waltz abruptly shifts the tone from the bright Hollywood/Middle European spectacle of Act II to film noir in Act III, monochromatic and misty on an empty stage, and all of a sudden mystical, with Wagner's soaring choral hymn of atonement and redemption. The dancing is once again sublime. When the stage turns blood-red with the return of the Venusberg music (and the welcome return of Prudenskaya), we have a superb example of the dramatic potential of dance.

I'm so pleased that BelAir Classique makes generous clips of their productions available on YouTube. This will give you a good feel for the style of the production and its high musical standards, if not the final excellence of the Blu-ray disc.

Great Shakespeare and Korngold from North Carolina

Back in 2013 I reviewed an excellent CD of music by Erich Korngold for Much Ado About Nothing. This was a recording premiere of Korngold's complete music for Shakespeare's great comedy, played by the University of North Carolina School of Arts Symphony Orchestra conducted by John Mauceri. When I tweeted the review today, the 400th anniversary of Shakespeare's birth, Mauceri let me know that there was a television film online of the complete play with Korngold's music. This is really fabulous; great performances by these fine actors and musicians!

Friday, April 22, 2016

Appealing music from a meld of traditions

Here is new music that should appeal to a wide audience. Lydia Kakabadse has a melodic gift, and is able to present an interesting meld of musical traditions into immediately appealing music. Listen to this track from her new CD Cantica Sacra, to be released on May 13, 2016.

Kakabadse's musical heritage comes from her Russian/Georgian father and her Greek/Austrian mother, and from her Greek/Russian Orthodox faith. She was born and raised in Cheshire, so the English choral tradition is part of this appealing mix. The music included in this CD is direct and clear, but with exotic overtones, sounding like Orthodox chants or Vaughan Williams' G Minor Mass one minute, and Carl Orff or 1940s Hollywood fantasy the next. The music is often serious but never bleak, and the mood is often broken by a sprightly tune, like a ray of sunshine in a dark church. The singing by the Alumni of the Choir of Clare College Cambridge, under the direction of Graham Ross, is outstanding. They're helped out by an excellent instrumental group, and some expert sound engineering. This disc is highly recommended; I look forward to more music from this fascinating composer.

Wednesday, April 20, 2016

A fine recording of a chamber music classic

Rebecca Clarke's Viola Sonata has been extraordinarily well represented on disc. Here are the violists who I came up with in a quick search:

- Matthew Jones, Naxos

- Philip Dukes, Naxos

- Vladimir Bukac, Calliope

- Tabea Zimmermann, Myrios

- Konstantin Selheim, Musicaphon

- Barbara Westphal, Bridge

- Barbara Buntrock, Avi

- Yizhak Schotten, Crystal

- Naoko Shimizu, Meister

- Christine Rutledge, Centaur

- Robert Glazer, Centaur

- Adrien La Marca, La Dolce Volta

- Peijun Xu, Ars Production

- Vidor Nagy, Audite

- Garfield Jackson, ASV

- Philip Dukes, Gamut

- Helen Callus, ASV

That's a lot! Shostakovich's Viola Sonata may have more, but I don't imagine there are any others from the 20th century with as many. Ernest Bloch's fine Viola Sonata, which tied with Clarke's in the Berkshire Chamber Music Festival's competition organized by the great music patron Elizabeth Sprague Coolidge, has only half a dozen.

It's no wonder this is such a popular work. It's a compact, expressive work, alternately intense and tender. It has the shifting harmonies and complex rhythms of Debussy. And it's beautifully played by Duo Runya, violist Diana Bonatesta and her pianist sister Arianna. The disc is well-filled with interesting shorter pieces that show off Clarke's versatility and charm. A highlight is the Passacaglia on an Old English Tune (by Tallis), which is reminiscent of one of the staples of the violist's repertoire, Johan Halvorsen's 1893 arrangement for violin and viola of a Handel Passacaglia.

There are a number of non-interpretive things I found really special about this disc. The first is the outstanding essay by Elisabetta Righini in the liner notes, a model of an in-depth study of a composer that many might not know well. Righini acknowledges the work of the Rebecca Clarke Society in her well-researched essay; those wanting to learn more should check out their website. Kudos should go as well to Beverley K. Drabsch for her fluent, idiomatic translation. Let's face it, record companies don't always get this particular facet of the recording process 100% right. And the recording is outstanding. Alessandro Simonetto's production and engineering follows Aevea's philosophy of minimum technical involvement in the project once the performances are complete. This entire project is a major accomplishment, a happy combination of musical talent, marketing and technology that will only boost the rapidly growing reputation of Rebecca Clarke.

Monday, April 18, 2016

Elastic, buoyant, ravishing music

This new CD from Glossa, to be released on April 29, 2016, was recorded at the Bela Bartok Concert Hall in Budapest with Hungarian singers, instrumentalists and conductor, but it sounds as authentically French as any recent recording I've heard. This is gorgeous music, and it's hard to believe it's not as popular as Rameau or Handel. In fact, I believe three of these Grands Motets are recording premieres, though there's no indication on the album cover.

Jean-Joseph de Mondonville was born, or at least baptized, on Christmas Day, 1711, which puts him in the generation behind Jean-Philippe Rameau. He was relatively productive as an instrumental and stage composer, but my favourite of his works are the sacred Grands Motets, only nine of which have survived. Judging by the quality of this music, the missing eight Motets are a great loss to the world of music. Of the four Motets included on this disc only one, De profundis, a setting of Psalm 129 from 1748, has been recorded before, as far as I can tell. This work is included in both Edward Higginbottom's 1999 Hyperion disc with Oxford New College Choir, and William Christie's 1997 Erato disc with Les Arts Florissants. I wish I could play the Purcell Choir version, but it's not available on Spotify yet. But I wanted those who don't know Mondonville's Motets to hear what ravishing music this is:

I actually much prefer the Purcell Choir/Orfeo Orchestra version under György Vashegyi to Christie's, as fine as it is. This new disc is fresher and lighter and more alive. Mondonville has such a dancing sound, "the rhythmical elasticity and buoyancy" in John Eliot Gardiner's words, of Baroque music. I like to think that after a hard day at the Concert Spirituel, Mondonville would take his wig off, let his hair down, and play some jazz with his friends. You can hear it in this music.

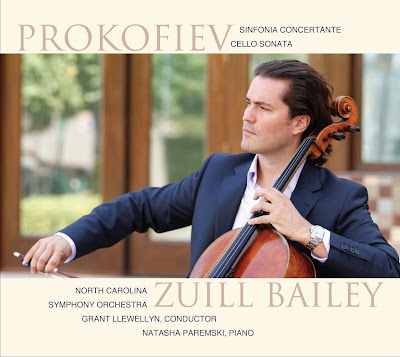

Intensity in concert, and in the studio

Cellist Zuill Bailey repeats almost exactly the formula that won raves from the critics in his 2014 Telarc recording of cello music by Benjamin Britten. That included the Symphony-Concerto and a Cello Sonata, as does this new Steinway disc of music by Sergei Prokofiev, due to be released on April 29, 2016. Bailey has the same supporting cast as well: the North Carolina Symphony conducted by Grant Llewellyn, and in the Sonata, pianist Natasha Paremski. The concerted works of both discs were recorded live at the Meymandi Concert Hall in Raleigh, while the sonatas come from the studio.

Way back in 2002 Bailey gave a wide-ranging interview with Tim Janof of the Internet Cello Society, in which he talked about the cello recordings that he especially loved. I'm not surprised with his choice of Rostropovich's famous recording of the Sinfonia Concertante with the Royal Philharmonic Orchestra and Sir Malcolm Sargent. Bailey and Llewellyn follow the great Russian/English team in terms of tempi, which tend to be a bit brisker than other recordings (especially Ma's, with Maazel in Pittsburgh). The cello is brought quite far forward, front and centre, in the recording, though, putting the emphasis more on the Concertante than the Sinfonia. It's an especially fine live recording, though, with that electric feeling you sometimes get in the concert hall. There's no sign of the audience, even at the end, which is different from the nine minutes of applause included in the latest recording from Atlanta.

This great work is extremely well served on disc. I listened to bits of a dozen versions, and all of the Rostropovich, Ma, Harrell, and Wallfisch, and marvelled at the way great and modest cellists could differ in small and large ways while still sounding so musical. The lovely tone of Bailey's venerable instrument - the 1693 Goffriller played by Mischa Schneider for three decades in the Budapest String Quartet - and Bailey's confident mastery of the work, puts this recording in the same league as those masters, with the very fine orchestral playing of the Carolinians very nearly up to the Royal Philharmonic, Pittsburgh or Liverpool orchestras.

I shouldn't forget the 1949 Sonata, which is fine indeed. Prokofiev, who had recently been charged with formalism in music, did not know if he'd ever have his music performed again, or worse. So he forgets about impressive effects to wow the audience; this is more like a personal working out of things in his brain. And what a brain! Bailey and Paremski (again, an equal musical partner) keep their eyes down and the feeling intense, eschewing obvious effects in favour of the work's bleak architecture.

In the world of the recording star you're always moving on to the next project. I follow Bailey on Twitter (as should you), and on April 16, 2016 he tweeted about the latest live recording project with the North Carolina Symphony, conductor Grant Llewellyn, and violinist Philippe Quint: the Brahms Double Concerto. I'm looking forward to this recording!

|

| Bailey, Llewellyn & Quint with the NC Symphony, from Bailey's Facebook page. |

Sunday, April 17, 2016

Ducklings and violin sonatas

I'm interested in the idea of musical imprinting: based on an analogy with the idea, borrowed from psychology, "of any kind of phase-sensitive learning (learning occurring at a particular age or a particular life stage) that is rapid and apparently independent of the consequences of behavior". I have a special link with the music of the Dave Clark Five in the same way that the duckling has formed a special link with the poor cat in this animated gif:

For some reason most of the online discussions I've read on this topic so far talk about this issue in relation to popular music. My link with the Dave Clark Five is indeed special, since in all likelihood only those who were young teenagers when Glad All Over was a hit would have any kind of positive response to this music today. Thus you can bet that most DC5 fans nowadays are likely be sixty-somethings, like me.

But of course there's imprinting going on in classical music as well. In my late teens our mailman delivered a five-LP set of Beethoven's music every month, recorded by Deutsche Grammophon, in the Time-Life Beethoven Bicentennial Collection. Month after month (17 of them) of great music, even towards the end when I opened up an album of the master's Irish and Scottish Folk Song arrangements, which I've loved ever since.

This resulted in a weird bias towards Beethoven in my music history knowledge. Constantly repeated listening imprinted on me the particular performances. Today I'm likely to listen to Beethoven symphonies conducted by John Eliot Gardiner or Jordi Savall or Gustavo Dudamel, but the right sound, the proper sound for Beethoven's symphonies is Herbert von Karajan. I tend to dislike most of Karajan's music, and I quite despise him as a man. But when I think "Beethoven Symphony" in my mind, I hear the Austrian jet-setter recording this in the DGG studio in 1962:

So the piano sonatas are little ducklings running through my brain after Wilhelm Kempff. The string quartets template is by the Amadeus, the cello sonatas by Fournier & Kempff. And the violin sonatas, which I loved from the beginning, were from the 1970 recording by Wilhelm Kempff, again, and 2016's Centenary Boy Yehudi Menuhin. Listening to one sonata at a time this music might be revolutionary and dramatic, or vulgar and clever, or just heart-breakingly sad. Listening to them all at once, from op. 12 no. 1 to op. 96, which takes four hours, is like watching a full season of The Wire, or reading The Golden Bowl.

Why the Trip Down Memory Lane before I talk about the album in question, the re-issue of Jane Coop and Andrew Dawes' 2001 Beethoven Violin Sonatas? Well, it's partly because the TDML is part of my schtick by now, but it's also to set up this: when I compared Coop & Dawes to Menuhin & Kempff, I often preferred them to the template in my head. When I preferred the earlier version, I could still admire the decisions the Canadian musicians had made. Music of this quality is as far as it can possibly be from a zero-sum game, so there's plenty of room for Perlman and Ashkenazy, or Kremer and Argerich, or many others. But to have a recording that's new to me push around one of those old imprints? Maybe the brain is indeed more plastic than we used to think. Maybe all that Sudoku is paying off!

I loved this re-release a lot. Hope I made that clear! Here's the first movement of the Spring Sonata, with leaves and blossoms bursting:

The sound of this recording is full, sounding of an open, reverberant space. It was recorded at the First Nations Longhouse at the University of British Columbia, an amazing building. I won't make any claims for a special spiritual connection between Beethoven and the Longhouse, but at the very least it's a space where two exceptional musicians made great music together.

Friday, April 15, 2016

Swan song

The story behind this album is an intriguing one. This is the final concert Robert Shaw conducted as Music Director with the Atlanta Symphony Orchestra and Chorus, from May 21, 1988. In an indication of how much he was loved in Atlanta, there's a full track of applause after the Beethoven symphony: an amazing 8 minutes and 41 seconds of it! Shaw continued as Music Director Emeritus and Conductor Laureate, and though he made many recordings for Teldarc with the ASO, he never had a chance to record the 9th Symphony. Telarc's founding producer Robert Woods was planning just such a recording in 1999, but the Maestro died months before the sessions were to begin. We're lucky to have this disc, a digital transfer of the unedited concert performance, and published just in time for the Shaw Centennial later this month.

Many years before a very young Shaw had prepared the chorus for Toscanini, for an NBC Symphony recording of the 9th Symphony. In a heartfelt tribute written soon after Robert Shaw's death in January 1999 for the Atlanta Journal and Constitution, Wendell Brock tells a story of how Toscanini, calling the young choral conductor 'maestro', complained about Beethoven's 9th Symphony:

"You know, maestro, I never have had a good performance." He said almost always the soloists are bad, and he said sometimes the chorus is behind, and the orchestra doesn’t always play together, and I never feel equal to this piece.

After Shaw's careful preparation of the chorus, Toscanini was pleased with the results: "Maestro, this is the first time in my life I’ve ever heard it done." Then, Shaw said, "Of course we all began to cry!"

In another story Brock tells how Shaw would write a formal letter to his choristers after each rehearsal, headed "Dear People". After a rehearsal of Beethoven's 9th Symphony he had this to say to his singers:

Our tenors are adolescent. Our altos have not passed puberty. Our sopranos trip their dainty ballet of coloratura decorum, and our basses woof their wittle gway woofs all the way home.... Get your backs and bellies into it! You can’t sing Beethoven from the neck up - you’ll bleed! Beethoven is not precious. He’s prodigal as hell. He tramples all over nicety. He’s ugly, heroic; he roars, he lusts after beauty, he rages after nobility. Be ye not temperate!

Rather than Shaw's legendary control over his musicians, it's this fire that dominates the final movement of Shaw's 9th on this new disc, from a lusty live performance. No wonder there was such an emotional response to the performance of the 9th at the Festspielhaus in East Berlin, during Shaw's tour of Europe with the ASO in 1988. This is music that runs through Shaw's career, and it runs in his veins.

Shaw came late to, and, he always felt, was somewhat musically unprepared for each new stage in his evolution from Glee Club Captain to Choral Conductor to Symphony Orchestra Music Director. In every case, though, he brought his game up to a very high level. It's not only the voices that shine in this recording; all the music shines in a way that's almost beyond criticism. There's more than an hour of white-hot music on this disc, along with 8 minutes and 41 seconds of love from Atlanta.

The pain of unending longing

Just as Orpheus’ lyre opened the gates of the underworld, music unlocks for mankind an unknown realm—a world with nothing in common with the surrounding outer world of the senses. Here we abandon definite feelings and surrender to an inexpressible longing....Only a week ago I was quoting E.T.A. Hoffmann's 1813 essay "Beethoven’s Instrumental

Music", in a review of a fine recording of Hoffmann's Symphony. But E.T.A. is at best only a minor composer; it's really in literature that he made his mark. The Beethoven essay is a landmark of music journalism because of its timing; it was an early appreciation of the cosmic significance of the Fifth Symphony. But the master of fantasy Hoffmann paints such a fantastic picture of why instrumental music is so romantic. Here's where he turns on the big guns:

Glowing rays shoot through the deep night of this realm, and we sense giant shadows surging to and fro, closing in on us until they destroy us, but not the pain of unending longing in which every desire that has risen quickly in joyful tones sinks and expires.Fifteen years ago Jane Coop rounded up a first group of especially romantic piano pieces, and CBC Records published it in their Musica Viva series. It's been a popular album since then (as was volume 2), and you can still order it from Amazon as a CD-R or on MP3. But on April 29, 2016, Skylark Music is re-releasing this disc, which is excellent news.

The music Coop has chosen comes from the gods of High Romanticism, Chopin, Schumann, Liszt, Mendelssohn, Brahms; the special god who perfectly distilled Romanticism, Debussy; and a late master who turned Romanticism up to 11, Rachmaninoff. Is there a more perfect piece to express "the pain of unending longing" than Brahms' A major Intermezzo, op. 118, no. 2? Nope; it always breaks my heart!

And is there a more perfect final quote from E.T.A. Hoffmann to end this review by letting everyone know how touched I am by Coop's playing? No, there isn't.

Romantic taste is rare, romantic talent even rarer, and perhaps for this reason there are so few who are able to sweep the lyre with tones that unveil the wonderful realm of the romantic.

Wednesday, April 13, 2016

A unique sound-world

I'm a bit late to the party here. Everyone is talking about Peter-Anthony Togni's new opera Isis and Osiris, which recently had its premiere in Toronto. I'm hoping a CD, or better yet, a DVD/Blu-ray, will be forthcoming. This disc of Responsio was released by the excellent Canadian label ATMA Classique last September, but somehow I missed it. It was nominated for a 2016 Juno award (Canada's version of the Grammys).

The sound-world of Peter-Anthony Togni's Responsio is completely unique. The great 14th century masterpiece Messe de Nostre Dame by Guillaume de Machaut is completely enveloped in the 21st century sound of a composer emerging as one of Canada's greats. A perfectly-integrated quartet of great solo voices - Suzie LeBlanc, Andrea Ludwig, Charles Daniels and John Potter - is likewise surrounded by the amazing sounds that emerge from Jeff Reilly's bass clarinet. Here's an instrument that we didn't know we were missing! Reilly, by the way, doubles as producer on the disc, and nails the technical aspects of the recording while doing exactly the same musically.

When I first listened to this music I imagined the musicians in the beautiful space pictured on the CD cover: the Cathedral at Reims, where Machaut probably composed his Messe, some time around 1365. The recording was actually made at the Eglise St. Bernard, on the Yarmouth and Acadian Shores in lovely Nova Scotia. I really regret missing visiting this church on our Maritimes trip last summer. We should have taken Highway 1 instead of the faster 101 between Weymouth and Yarmouth!

You can get a feel for that space in this excellent promotional video:

One of my favourite musical trends relating to what we used to call Early Music is the interaction between old and new music. I agree with Stephen Hough, in his recent blog post at The Telegraph: we needn't apologize for presenting classic musical works. But:

If our concert halls are like museums for music that doesn't mean we should just unthinkingly trundle out the same pieces every season. We might need to hang or light a painting better, display it alongside something different, rethink our education programmes, explain its beauty and significance more imaginatively, send it to the restorers.We absolutely have to take every opportunity to make those connections between old and new. This might involve programming old and new music on the same program or recording, or it might be an organic re-mix like this thoughtful, vital work, which I believe will be seen as an important Canadian composition for a long, long time.

And speaking of museums, if I hurry with this review, I can provide some useful information to Montrealers. The original cast will be performing Responsio at one of my favourite museums in the world, the Montreal Museum of Fine Arts on April 20, 2016. Wish I could be there!

Saturday, April 9, 2016

Light and alive; tasteful and thoughtful

The Mozart piano concertos are, along with Bach's Brandenburg Concertos, my absolute go-to music. I play them when I'm feeling low, or when I'm especially happy. Or when I'm feeling somewhere in between; you get the picture! Few cycles have given me as much pleasure as the one which is only now coming to a close. It began in November 2010, when BIS recorded fortepianist Ronald Brautigam and Die Kölner Akademie conducted by Michael Alexander Willens in their first disc of the series. The series was front-loaded, with the best concertos already recorded by the end of last year. This penultimate disc, released this week, and the final disc which I presume will come this fall, are bound to be a trifle anti-climactic. But early Mozart has its charms, and this repertoire has an extra interest I'll get to in a moment. This isn't profound music, but it has a very real, if slightly superficial, appeal.

The numbering of the piano concertos is a bit complicated. The two- and three-piano concertos are included in the standard list of 27, and numbers 1-4 are actually arrangements by Mozart of contemporary piano sonatas by other composers. Those four, by the way, will be included in the final disc in the BIS series. The current disc thus includes the first piano concerto Mozart actually wrote, number 5, K. 175. It's a marvellous trumpets-and-drums romp with a flashy solo part Mozart wrote for himself. One of the things that impresses me the most about this work is its effortless distillation of opera buffa into a concert work. Comedy, they say, is hard, but for a 17-year-old to make such a comic soufflé without it collapsing: astounding!

Of course Brautigam and Willens and the Cologne musicians have their part to play in keeping things so light and alive. They shine as well in the sixth concerto, K.238, which is much less flashy and a trifle more erudite. This is a tasteful and thoughtful performance of a work which begins to show the more serious side of Mozart's music.

Finally we come to three intriguing pasticcios, as they were termed, arrangements of three solo sonatas by a close musical mentor of Mozart's in London, Johann Christian Bach. These are not the arrangements I mentioned before, and they have no official numbers in the series of 27, but their Köchel number of 107 gives an idea of where they fit in Mozart's catalogue. They have considerable charm, and it's worth listening to both the originals and Mozart's arrangements. Back in 2007 Hanssler Classic released a disc with pianist Gerrit Zitterbart that combined the three concertos and sonatas, making it easy to compare the music. Brautigam easily out-classes Zitterbart, by the way, though I regret the loss of the "Scotch snap" in his version of the Theme and Variations second movement of the G major concerto. I've always loved hearing that Hibernian lilt in English music of the 18th century.

One of the things I discovered when I listened carefully to the J.C. Bach sonatas was the high quality of this source material. These are important works, just below the level of Haydn, and deserving careful attention from pianists and listeners. It's no wonder Mozart wanted to rework this music to make an impression with connoisseurs. I recommend both Sophie Yates on Chandos and Rachel Heard in a new Naxos CD in this repertoire (Mozart arranged number 2, 3, and 4 of Bach's six sonatas). Here's Heard with the Scotch snap!

Trumpets Three-Wise Silverflamed

|

| Ludwig Van and his acolyte Alex (Malcolm McDowell), in Kubrick's film A Clockwork Orange |

Oh it was gorgeousness and gorgeosity made flesh. The trombones crunched redgold under my bed, and behind my gulliver the trumpets three-wise silverflamed, and there by the door the timps rolling through my guts and out again crunched like candy thunder. Oh, it was wonder of wonders. And then, a bird of like rarest spun heavenmetal, or like silvery wine flowing in a spaceship, gravity all nonsense now, came the violin solo above all the other strings, and those strings were like a cage of silk round my bed. Then flute and oboe bored, like worms of like platinum, into the thick thick toffee gold and silver. I was in such bliss, my brothers.This, of course, is A Clockwork Orange, the 1962 novel by Anthony Burgess, which combines the language experiments of Joyce and Spike Milligan with the dystopias of Huxley and Orwell. Music looms large in the novel, as it did in Burgess's imagination, if not so much in his life. "I wish people would think of me as a musician who writes novels," he said, "instead of a novelist who writes music on the side." But this was not to be. Though he spent much more time writing music late in his life, it was always seen as a side-line. He never gained traction as a composer. Now, nearly 25 years after his death, there are only a few discs of his music available on CD and the streaming services. Is it time for new interest in Burgess as composer?

It's the Ivy League to the rescue! Paul Phillips, Director of Orchestras and Chamber Music at Brown University, has put together the first CD of Burgess orchestral music. Naxos, with its tradition of musical excavation, was the obvious label for the project. Phillips, in his excellent liner notes, characterizes this music as "a hybrid of Holst and Hindemith", but there are many reminiscences as well of the honourable tradition of English Light Music: Percy Grainger and Eric Coates especially. And when things get more dissonant, I'm reminded of French composers like Milhaud and Poulenc, though curiously nothing sounds as English (here Vaughan Williams and even Elgar) as the Marche pour une révolution, written to mark the bicentennial of the French Revolution.

Though this is all, for now, when it comes to the orchestral music on disc, there is a concert recording from the BBC that's up on YouTube. The excellent Juanjo Mena conducts the BBC Philharmonic in Burgess's tribute to his home town, A Manchester Overture.

With that 25th anniversary of his death coming next year, it seems like a good time to sit back and take a look at the artistic life work of Anthony Burgess as a whole. The unfortunate over-sized role of A Clockwork Orange due to the notoriety of Kubrick's film has given us a skewed picture of Burgess the novelist. Hopefully there might be a new balance as well between Burgess the writer and the composer, though judging by what we have so far, I don't believe things will change too awfully much. It's encouraging to see a new disc of piano music coming this summer, and I'm hoping Phillips might record the Third Symphony for Naxos in the future. My droogs and I might listen to some of the music occasionally, but for me Anthony Burgess will still be the author of the Enderby series and Earthly Powers.

|

| This new disc from Richard Casey will be released on June 3, 2016. |

Friday, April 8, 2016

The Romantic classicist

When I started listening to the new Naxos CD of music by Anthony Burgess for review (coming soon), I began to wonder about other writers who were also musicians. I think the best is still Paul Bowles (a new CD of whose I praised last week), but E.T.A. Hoffmann gives him a run for the money.

It's interesting how Hoffmann, who helped to popularize the whole idea of Romanticism, is more of a classicist when it comes to his music. "Haydn shall be my master," he said, and you can hear the strong influence of Haydn's London Symphonies in the main work on this disc from 2015. There are novel effects, to be sure, but this work written in Warsaw in 1806 seems more from the 18th century than the 19th. The two overtures on the disc, to Hoffmann's operas Undine and Aurora, were written in 1812 and 1814. This is about the same time as Hoffmann's famous article "Beethoven’s Instrumental Music" (1813), one of the greatest pieces of writing about music.

Just as Orpheus’ lyre opened the gates of the underworld, music unlocks for mankind an unknown realm—a world with nothing in common with the surrounding outer world of the senses. Here we abandon definite feelings and surrender to an inexpressible longing....

Thus Beethoven’s instrumental music opens to us the realm of the monstrous and immeasurable. Glowing rays shoot through the deep night of this realm, and we sense giant shadows surging to and fro, closing in on us until they destroy us, but not the pain of unending longing in which every desire that has risen quickly in joyful tones sinks and expires. Only with this pain of love, hope, joy—which consumes but does not destroy, which would burst asunder our breasts with a mightily impassioned chord—we live on, enchanted seers of the ghostly world!But listen to the overture to Undine; it mainly looks back to Mozart and Gluck, though if you squint, you can see it looking ahead a bit to Weber and Mendelssohn.

Romantic taste is rare, romantic talent even rarer, and perhaps for this reason there are so few who are able to sweep the lyre with tones that unveil the wonderful realm of the romantic.

Not that there's anything wrong with that. That Hoffmann's musical world was a bit more limited than his broad-ranging literary universe, based on his nearly boundless imagination, is only to be expected. Hoffmann was a very practical man of the theatre. Besides writing operas, he designed scenery, conducted the music, and helped in the operations of the opera house business. Add to all of this his musical journalism, his legal duties, and a significant dabbling in the visual arts (including very fine work as a caricaturist), and you can cut the guy some slack. I find Hoffmann such an appealing bloke; I'd love to go down to the pub and share a tankard of ale with him some time.

|

| Besides his musical & literary talents, Hoffmann was a fine draftsman. |

I should mention a couple of other things. First the coupling of Friedrich Witt's Sinfonia, written in 1809. This is a well-crafted work, again very much in the Haydn style. I find it interesting that Haydn loomed so large at the time, Mozart seemingly forgotten, and Beethoven passed by without remark in this symphony. If Witt had the extra-musical connections that Hoffmann had we'd all know his music much better, and I'd give him more space than this postscript.

As to the performances on the disc, they are exemplary, as one would expect from the Die Kölner Akademie & Michael Alexander Willens, who have presented so many stylish recordings, most especially the superb BIS cycle of Mozart Piano Concertos with Ronald Brautigam.

Tuesday, April 5, 2016

New! Improved!

Though as far as I know 17th century Venetians didn't have cereal or soap boxes with "NEW!" labels, they were still big on novelty. Aficionados of music looked for the "Stil Moderno" tag when it came to new music:

|

| Score from IMSLP. |

And the thing is, this music can sound pretty novel even today. There's something fresh and unexpected about the way Dario Castello crafts his melodies, his dramatic recitatives, and even those nods to the past, his strict polyphonic sections. You'll notice that Castello is billed in the title page of the Sonate Concertante as "Musico Della Serenissima Signoria di Venetia in S. Marco, & Capo di Compagnia de Instrumenti", which puts him in St. Mark's Cathedral during the time that Claudio Monteverdi was in charge of the music there. This is indeed in the "Modern Style", perhaps even "Bordo d'attacco", which Google Translate tells me is Italian for "Leading Edge".

Some of the freshness and verve I hear in the music must come from the musicians of Musica Fiata, and their conductor Roland Wilson. Wilson and his musicians would need to make decisions about orchestration and interpretation, since the score is sometimes a bit generic:

Though Musica Fiata have recorded Venetian music in the past, I know them best playing music from Germany and Austria: Fux, Schutz, Schein and Rosenmuller. Their 2013 Bach Luther Cantatas disc for Deutsche Harmonia Mundi was outstanding. But this new disc of Castello's amazing music demonstrates that nothing is lost in the transalpine journey. The CD will be released on April 8, 2016; pre-order or stand in line at Amazon.com early on the 8th (ha!) to get yours.

Sunday, April 3, 2016

The ideal of enlightened transcendence

Just over a year ago I reviewed the first volume in Tempesta di Mare's Comédie et Tragédie series. I especially enjoyed Jean-Fery Rebel’s Les Elements, but the entire disc gave me a strong feeling of the civilized order of Enlightment Age music. We have more of the same in this second disc, from three different composers living in the same world, and the Philadelphia-based baroque ensemble Tempesta di Mare. I wondered if the temperature of the first disc was a bit cool, and I wonder the same about this one. In Leclair's suite from Scylla et Glaucus, the Airs des demons don't sound especially demonic. Red Priest are perhaps a bit over the top (their album is called Nightmare in Venice), but this Air has got drive:

However, I'm always ready to hear the siren call of Enlightenment, of civilization and order. The theatre in 17th century France was full of spectacle and engines bearing Gods and artificial lightning and thunder (the equivalent of today's "special effects"). There was underlying it all, though, this wonderful ideal, part ancient and part modern, of enlightened transcendence. Leclair's music, and Charpentier's, and especially Rameau's, embodies this ideal. As fun as the "mad, bad and deliciously dangerous" shiny bits can be, Tempesta di Mare delivers something more valuable.

An impressive debut

This is Marita Solberg's debut solo album, and it's a real winner. I know her only from two Grieg discs on BIS: the complete Peer Gynt from 2009, and Grieg Orchestral Songs from 2010. Listening to those again, it's clear to see that with such a strong, pure voice Solberg had a great future in opera. I'm actually a bit surprised that Solveig's Song isn't included in the this program; it seems to be a bit of a signature song:

Other than that omission, I'm impressed with the program, which shows off Solberg's voice and her range.

The aria by Catalani from La Wally, made famous in Jean-Jacques Beineix's 1981 film Diva, is a great opener. It shows off the powerful yet creamy quality of Solberg's voice while the more controlled Mozart arias that follow, the Countess's arias Dove sono and Porgi amor from The Marriage of Figaro, demonstrate her dramatic intelligence. Two other songs stand out: the drop-dead gorgeous Song to the moon from Dvorak's Rusalka, and an affecting Ave Maria from Verdi's Otello. The strong accompaniment from conductor John Fiore and the Norwegian National Opera Orchestra contributes to an outstanding disc, and they're given their own little encore near the end: the beautiful Interlude from Richard Strauss's Die Liebe der Danae.

An impressive, nearly perfect, debut!

Available for pre-order at Amazon; the release date is April 8, 2016.

Saturday, April 2, 2016

Greatness in parodies and covers

In October and November of 1967 Bob Dylan recorded his album John Wesley Harding. The critical response to the album when it was released on December 27 was universally positive, and the album was a big success, hitting #2 on the album charts in the US, and #1 in the UK.

Jimi Hendrix was in London in early 1968, recording at Olympic Studios, and on January 21st he heard a tape of Dylan's song All Along the Watchtower. Hendrix immediately began recording his first versions of the song, putting multiple takes on tape, and later in New York, overdubbing and remixing until he released the celebrated single on September 21, 1968.

Dylan talks about the song in an interview published in the Fort-Lauderdale, Sun Sentinel in July 29, 1995:

Let's skip back a couple of centuries, to Naples in 1736. Giovanni Battista Pergolesi has just written a new setting, in the modern style, of the Stabat Mater, for an annual Good Friday service. Though Pergolesi died within a couple of months (indeed, only two weeks before Good Friday, and at the absurdly early age of 26), the work was an immediate hit. Its fame reached Germany, and in the mid-1740s J.S. Bach wrote a transcription (which has also been called a parody, in the earlier musical sense of the word), setting it to the words of Psalm 51.

Here is Pergolesi's Vidit Suum Dulcem Natum:

These are heartbreaking words:

Pergolesi's ending is particularly touching. As Christ nears his end, the strings give a last angry forte cry at "forsaken", and then play sotto voce to the end of the movement. This anticipates the soprano's final anguished line "as He gave up the spirit", sung in whole notes and, again, sotto voce. This is music drama of the highest order.

When Bach adapted this movement, the words from his Psalm had much less pathos, and more mystery:

Bach does some cool things with his source material in this movement. Most importantly he recognizes the greatness of the original; the beautiful melodies and suspensions of the durezze e ligature style remain. Bach latches onto a cool figure that Pergolesi has the strings play starting in the third bar. "There's some mystery for my next bit," Bach might have thought. But Pergolesi doesn't come back to that very spacey riff.

So Bach gives the bit to the viola, which throughout Pergolesi's work has been stuck doubling the continuo, and lets it run with it. The movement becomes a soprano solo with viola obligatto.

This new version is no less affecting, and I'm hoping I'm not wildly off base when I make the analogy between Bach's viola and Jimi Hendrix's guitar solos. There is pathos in both the Pergolesi/Bach and Dylan/Hendrix stories. Pergolesi and Hendrix both died much too young. But musical greatness calls out to musical greatness, and the adaptive re-use of another artist's material can reach the same heights as original work.

Jimi Hendrix was in London in early 1968, recording at Olympic Studios, and on January 21st he heard a tape of Dylan's song All Along the Watchtower. Hendrix immediately began recording his first versions of the song, putting multiple takes on tape, and later in New York, overdubbing and remixing until he released the celebrated single on September 21, 1968.

Dylan talks about the song in an interview published in the Fort-Lauderdale, Sun Sentinel in July 29, 1995:

Q: How did you feel when you first heard Jimi Hendrix's version of "All Along the Watchtower"?

A: It overwhelmed me, really. He had such talent, he could find things inside a song and vigorously develop them. He found things that other people wouldn't think of finding in there. He probably improved upon it by the spaces he was using. I took license with the song from his version, actually, and continue to do it to this day.The Hendrix version of All Along the Watchtower has been called one of the greatest covers in popular music; it certainly has my vote.

Let's skip back a couple of centuries, to Naples in 1736. Giovanni Battista Pergolesi has just written a new setting, in the modern style, of the Stabat Mater, for an annual Good Friday service. Though Pergolesi died within a couple of months (indeed, only two weeks before Good Friday, and at the absurdly early age of 26), the work was an immediate hit. Its fame reached Germany, and in the mid-1740s J.S. Bach wrote a transcription (which has also been called a parody, in the earlier musical sense of the word), setting it to the words of Psalm 51.

Here is Pergolesi's Vidit Suum Dulcem Natum:

These are heartbreaking words:

Vidit suum dulcem natum

Morientem desolatum,

Dum emisit spiritum.

She saw her sweet Son(Translation)

dying, forsaken,

as He gave up the spirit.

Pergolesi's ending is particularly touching. As Christ nears his end, the strings give a last angry forte cry at "forsaken", and then play sotto voce to the end of the movement. This anticipates the soprano's final anguished line "as He gave up the spirit", sung in whole notes and, again, sotto voce. This is music drama of the highest order.

When Bach adapted this movement, the words from his Psalm had much less pathos, and more mystery:

Sieh, du willst die Wahrheit haben,

die geheimen Weisheitsgaben

hast du selbst mir offenbart.

See, you want the truth, and you yourself revealed to me((Translation: Vera Lucia Calabria)

the secrets of wisdom.

Bach does some cool things with his source material in this movement. Most importantly he recognizes the greatness of the original; the beautiful melodies and suspensions of the durezze e ligature style remain. Bach latches onto a cool figure that Pergolesi has the strings play starting in the third bar. "There's some mystery for my next bit," Bach might have thought. But Pergolesi doesn't come back to that very spacey riff.

So Bach gives the bit to the viola, which throughout Pergolesi's work has been stuck doubling the continuo, and lets it run with it. The movement becomes a soprano solo with viola obligatto.

This new version is no less affecting, and I'm hoping I'm not wildly off base when I make the analogy between Bach's viola and Jimi Hendrix's guitar solos. There is pathos in both the Pergolesi/Bach and Dylan/Hendrix stories. Pergolesi and Hendrix both died much too young. But musical greatness calls out to musical greatness, and the adaptive re-use of another artist's material can reach the same heights as original work.

Friday, April 1, 2016

Timeless stones come alive

|

| Photo by MarkusMark, published under a Creative Commons license. |

There's plenty of impressive music in this piece; its surprising how it can sparkle like the Barber of Seville and yet provide a full measure of drama and piety. In this production so much of the credit goes to conductor Francesco Quattrocchi, who has the enormous challenge of providing a cogent orchestral sound in such a huge volume as the interior of this massive church. It's the largest church in Italy, the fifth largest in the world. The singers are led by the great Ruggero Raimondi, but this is more an ensemble piece than a star vehicle. There are no weak links amongst the principal singers, though the acting in this semi-staged version set within a huge space is necessarily broad, to reach the audience as well as the HD cameras. The chorus is equally important, and comes through with flying colours. In the end we rely on Quattrocchi to marshall all of these resources - the fine solo singers and the excellent Veneranda Fabbrica del Duomo di Malano Orchestra and Chorus - while keeping them all in balance, acoustically, dramatically, and musically.

We come now to the thing that makes this really special: the production treats the Duomo interior, which somehow seems super-opulent while also being super-austere, as a giant stage set, and the new technology of video mapping, or projection mapping, turns the Duomo into a dynamic space that opens up the story. The timeless stones come alive and help to tell the story. This is the second time in the last couple of weeks I've ended up talking about new technologies when reviewing a new classical music disc; I love it!

This YouTube clip gives you only a hint of an idea of how impressive this is on a large HD screen with good 5.1 surround sound. For the full effect you'll have to buy the disc and see for yourself!

Subscribe to:

Comments (Atom)